The Return of the King - Historia Regum Britanniae

Truth is stranger than fiction

Then, at last, Brute calleth the island Britain, and his companions Britons, after his own name, for he was minded that his memory should be perpetuated in the derivation of the name.

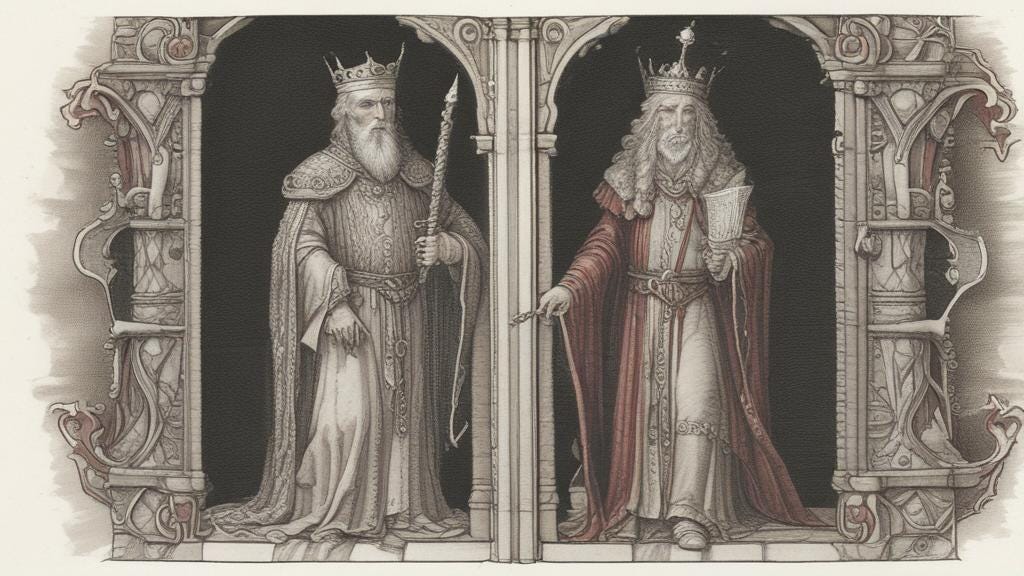

Recently, I have been reading through Geoffery of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae - History of the Kings of Britain - a pseudohistorical telling of the origin of the Britons spanning two thousand years up to the time of the Anglo-Saxon conquest. Beginning shortly after the fall of Troy, this legendarium follows the line of Brutus (or Brute), the great-grandson of the Trojan prince Aeneas. Indeed, the same Aeneas found within Virgil’s Aeneid, the progenitor of Rome. The descendants of this mighty people thread an epic of kings, queens, wars, heroes, villains, giants, and wizards through to the fabled King Arthur. The accounted history includes extraordinary figures such as Corineus, Queen Gwendolen, King Lear, Julius Caesar, Constantine, Uther Pendragon, Guinevere, and Merlin. Written in the mid-12th century, English bishop Geoffery of Monmouth set out to craft his compendium in such a way that was worthy of the rich history of that storied island. He begins his Historia by stating that not much has been preserved of the kings of the Britons before the Incarnation of Christ, but what has survived is filled with such venerable feats that they ought bear remembrance in perpetuity. After exploring much of the History of the Kings of Britain, I believe he is right.

However, if you look up anything about this book, be it reviews, analyses, critiques, or summaries, one ugly term is constantly repeated, often smugly; and it is one that I have just begrudgingly used myself: pseudohistorical. Commentators on this work will laud the narrative structure, the prose, the rich characters, and so on, but cannot refrain from underlining and prefacing their appreciation with the fact that, historically speaking, Geoffery’s Historia is anything but. A pretty tale that plays fast and loose with anachronism, myth, and pure fiction. “Historically worthless.” I take great umbrage with this perspective. In fact, I think it is worthless. Were I an inhabitant of the British Isles, what value or worth would I receive from some dry tome or monotoned academic reciting dead facts in a bulleted list? What advantage does my heritage gain in charting the Angles and Saxons’ migratory path to Britain as if they were birds? Why would I wish to consider Arthur a mere propaganda figure borne of a response to a time of Norman claimants, titles, and aristocracy? No more than an iron boot with a leg of religious dogma stepping on the poor proletariat. One online critic and self-proclaimed historian dared to say that “history doesn’t have a story, it’s just things that happened” when reflecting on Geoffery’s opus. May he keep his dead facts and arithmetic. Instead, I would offer a counter-perspective, the very same that Geoffery of Monmouth took when writing: the past is alive and it’s not just history: it’s our story. It is not dead; though, perhaps like Arthur in faraway Avalon, it is sleeping, ready to be roused and to make a triumphant return with Excalibur in hand.

All roads lead to Rome

‘By Hercules,’ saith he (Caesar), ‘we Romans and these Britons be of one ancestry, for we also do come of Trojan stock.’

As mentioned, the Historia begins with the birth of Brutus of Troy in Italy. A descendent of the displaced Aeneas, he too becomes exiled following the accidental murder of his father. After wandering the Mediterranean, Brutus ends up in Greece and falls in with a band of Trojan slaves. He quickly becomes their chieftain and catalyst for freedom, leading an exodus of the forsaken Trojans abroad. Travelling the coasts of North Africa and the Western Mediterranean, the company happens upon a derelict temple of Diana. Brutus here receives a prophecy that he will go on to lead his people to a promised land girded by raging seas. Then taking his fellow Trojans through Gaul, befriending tribes of men and waging war with others, Brutus eventually lands on what would become Britain. From there, too many stories and epic tales follow and I cannot do them justice by regaling them here. Suffice it to say, the Britons undergo approximately two thousand years of trials and tribulations, warring amongst themselves and defending against Picts, Scots, Danes, Saxons, and, of course, Romans, even unto making Julius Caesar himself turn his back. The Historia ends with the inevitable overtaking of the island by Saxons and Angles, the mortally wounded King Arthur is taken to Avalon and the remaining Britons recede into a sleep of their own.

Throughout the telling, Geoffery often alludes to other happenings in the world to help place his history. Most often, it is in the context of the biblical narrative, something all of his readers would be intimately aware of. For instance, when Brutus founded ‘New Troy’ or Trinovantum on the Thames - what would later become London - it is said that at that time Eli was priest in Judea and the Ark of the Covenant was taken by the Philistines; the sons of Hector reigned in Troy and Sylvius Aeneas reigned in Italy. It continues on in such fashion, charting its narrative alongside Samuel the prophet, Homer the poet, Saul and David, the Incarnation of Christ, and the travels of the apostles. An important addition, in my estimation. The reason being similar as to why I believe the story of Brutus is important; why the Romans too traced their ancestry back to the Trojan War; why losing the Eagle Standard was a fate worse than death; why the likes of modern Russia, Scotland, Italy, India and more hold that an apostle made their final home in their lands; why the West lays claim to ancient Greek and Roman authority as torchbearers: it calls us to participate in the world. It demands that we do indeed bear this torch, preserve its flame, and pass it on. In this perverse generation, we (or rather some of us) think we can snuff the flame out. Worse, some believe it is our duty to erase the past and cast down those mighty men who fought, bled, and died to lift us ever up. An easy thing to proclaim from our bequeathed vantage point, but fortunately a much harder thing to actually achieve.

What the insulated academic fails to realize is that having long lines of arbitrary points on a map is less important than having a long thread that stretches through time. From that perspective, it is no wonder why both Rome and Britain laid their roots in Troy. It was the oldest story those people could reach back into. Its narrative was the central maelstrom in which the cultures of the known world orbited around. It is what bound the men of that era together. It contextualized and made sense of the world they lived in. Much like the theme of pseudohistory, what is relayed in many sources regarding the Trojan origin of Britain is the idea of legitimacy to rule. Though I do not doubt that plays its role, I can’t help but interpret that perspective as also cynical. One does not have to be well-versed in the stories of the past to see that honour, loyalty, and duty were considered some of the highest virtues. The later Britons in Geoffery’s Historia were not duped or deceived into serving false kings. They shared in the lineage and were devoted to its survival for their own sake. Until the modern age, no one would have ever suggested that history is not a story for all to partake in. It is a dangerous and false pretense and we’re seeing its effects today.

Corroborating our myths

In the science, evolution is a theory about changes; in the myth it is a fact about improvements. - C.S. Lewis

Our history is what grounds us in reality itself. Humans are narrative creatures; we know this fact well. One need not look beyond the simple question of ‘how was your day?’ to understand this. We are inundated with stories; they’re on the silver screen and in an impassioned retelling of how someone cut you off in traffic; the jokes you tell and that time you forgot your keys. Simply put, stories are the way we engage with the world. In fact, there is no other way. History, therefore, is by definition a story. It’s the meta-story and it fills all others. Yes, even down to the dead facts, such as the specific words we use, the weapons the Celts wielded, where a city was built, and where the Britons came from. There’s a story behind every object under the sun, and there are many stories behind the sun itself. Let the academic gladly boast of his knowledge of the heliocentric view, saying the earth merely orbits the sun on an axis - a simple fact. I will pay attention to this shallow way of thinking when someone can experience the earth orbiting the sun rather than the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. The latter reality shared between all humans since we first walked the earth. That’s not to say that secondary and material causality does not have its place, only that it is not the only place, and is often of least importance. The same goes for Brutus and his Britons.

If one were to travel back to the time of Geoffery of Monmouth and explain to him how we can disprove all that he has written because we can sequence the genes of the Britons and compare it to the genes of other peoples of the ancient world, he would have no way to engage with that information. He would look upon the traditions that filled his every day, gaze upon the statues and castles that surrounded him with their mystifying names and legendary status, and remember hearthside sagas, all while laughing us into shame. All he would have to say is ‘If King Arthur was not real, how then can I go and meet not one of my countrymen who has not heard of him?’ Let me be clear, when I argue that pseudohistory is true I do not mean allegorically or metaphorically. I mean it is true. As true as the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. The truth of a thing is the spirit behind it. Forensics is secondary; moreover, the forensics that I can never know and will never experience is less than secondary. But I can experience the history of Brutus. I can go and walk the very same hills and rivers he walked and be inspired by the spirit of the same stories he was inspired by. I believe we could all be enriched by this perspective, especially in this modern age.

The future isn’t what it used to be

O, but in those days was the British race worthy of all admiration, which had twice driven in flight before them him who had subjected the whole world beside unto himself, and even in defeat now withstood him whom no nation of the earth had been able to withstand, ready to die for their country and their freedom!

We have developed a bad habit of reducing a thing to its parts and satisfying ourselves with our bottom-up answers. Cultural history has not been immune to this devouring spirit. Consider modern architecture: no more do we build things that will last generations. Our buildings are not elevated with crafts of art, rather we just simply elevate them in height. Clear glass has replaced paint stains and even the lattice; houses of the same shape, colour, and size are neatly ordered in cul-de-sacs. Will we see cultural marvels like that of Stonehenge or the Great Pyramids again? Even how we count the days has been replaced with the drab description of before the common era and the common era - though much to the chagrin of many, the pivotal moment that defines such an era has an impossible grip. Statues are torn down, streets are renamed, and books are banned. In times past these would be replaced by some conqueror or prevailing culture; now, however, we have opted to replace them with nothing. Our heroes are dead we are told, and they weren’t really heroes at all. As far as I can tell, this is directly related to the same ideology levied against the Historia Regum Britanniae. Pretty as these things may have been, they are no longer real or were wrong and therefore “worthless”. The effect of this attempt to sever that same thread which ties us back to Brutus has in part unravelled us. Our history is our mirror. Choosing the light in which we perceive our past will reflect into the future. When nations bring their origin back to the great heroes at the beginning of time, they are revealing the spirit they wish to act out; to create and push further into our shared history. If we opt for the academic mind or view all that is past as an evil that should never have happened, invariably our future will be ennuied at best or at worst destructive.

If we view it as an honour to continue the struggle with reverence to how far we’ve come, we will continue to create such legends as the line of Brutus did. That doesn’t mean mistakes can’t be rectified; quite the contrary. It is the noble challenge of a great story to have the ability to improve upon the flaws our forefathers didn’t have the ability or freedom to change. We have to recognize the things that have always inspired us so that we can not merely live, but rather further our story to the limits of the greatest epics and most awesome legends. We are not so far gone that great people can no longer rise. Instead of saying “There’s no way that happened” may we learn to say “It is time to awaken sleeping Arthur and welcome the return of the king.”

Thanks for reading,

Sam